ERDC/CHL CHETN-II-44

September 2001

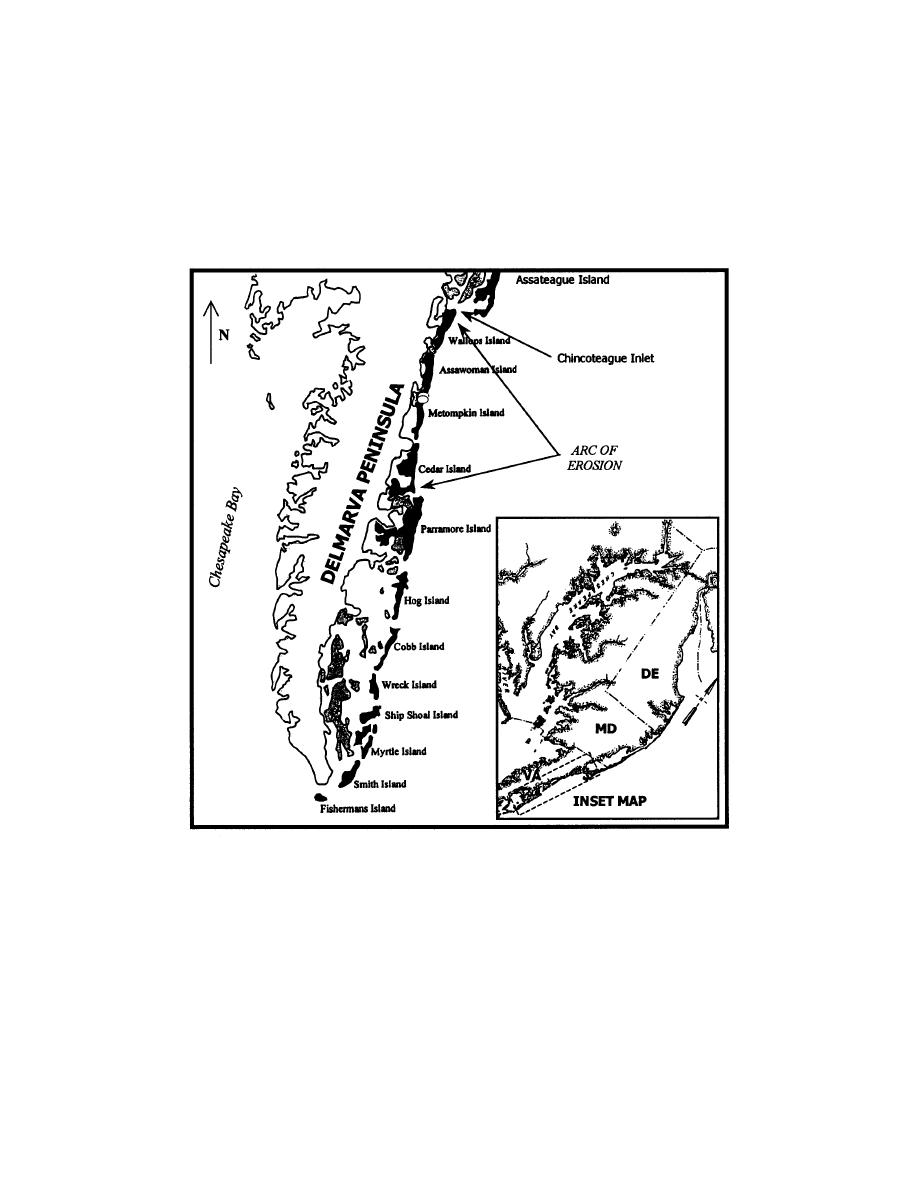

downdrift (e.g., Chincoteague Inlet, VA see Figure 4). In mesotidal conditions, inlet stability

and behavior have been shown to directly alter barrier island morphology. Dean and Work

(1993), Nummedal et al. (1977), FitzGerald, Hubbard, and Nummedal (1978), and Mehta (1996)

concluded that tidal inlets are responsible for most of the beach erosion along U.S. East Coast

barrier-island chains. Galgano (1998) demonstrated that nearly 70 percent of the shoreline along

the mid-Atlantic coast is significantly influenced (erosion or accretion) by tidal inlets.

Figure 4. Regional view and shoreline change rates in vicinity

of Chincoteague Inlet, VA

The literature indicates that beaches located directly downdrift of inlets experience significant

erosion and can be termed broadly as EHSs (e.g., Leatherman et al. 1987; Dean and Work 1993;

Douglas and Walther 1994; Fenster and Dolan 1996; Mehta 1996; Bruun 1996). These regional

EHSs, which typically measure 10-16 km in length (Galgano 1998), are not limited to inlets

stabilized by jetties. In fact, unstabilized or natural inlets can cause EHSs that extend laterally at

mega-scales, extending some 30-40 km downdrift (Finkelstein 1983; Galgano 1998).

Chincoteague Inlet (Figure 4) at the southern terminus of Assateague Island is one such example.

It is a naturally existing microtidal inlet and traps a large volume of longshore sediment

9

Previous Page

Previous Page