CETN-III-22

4/84

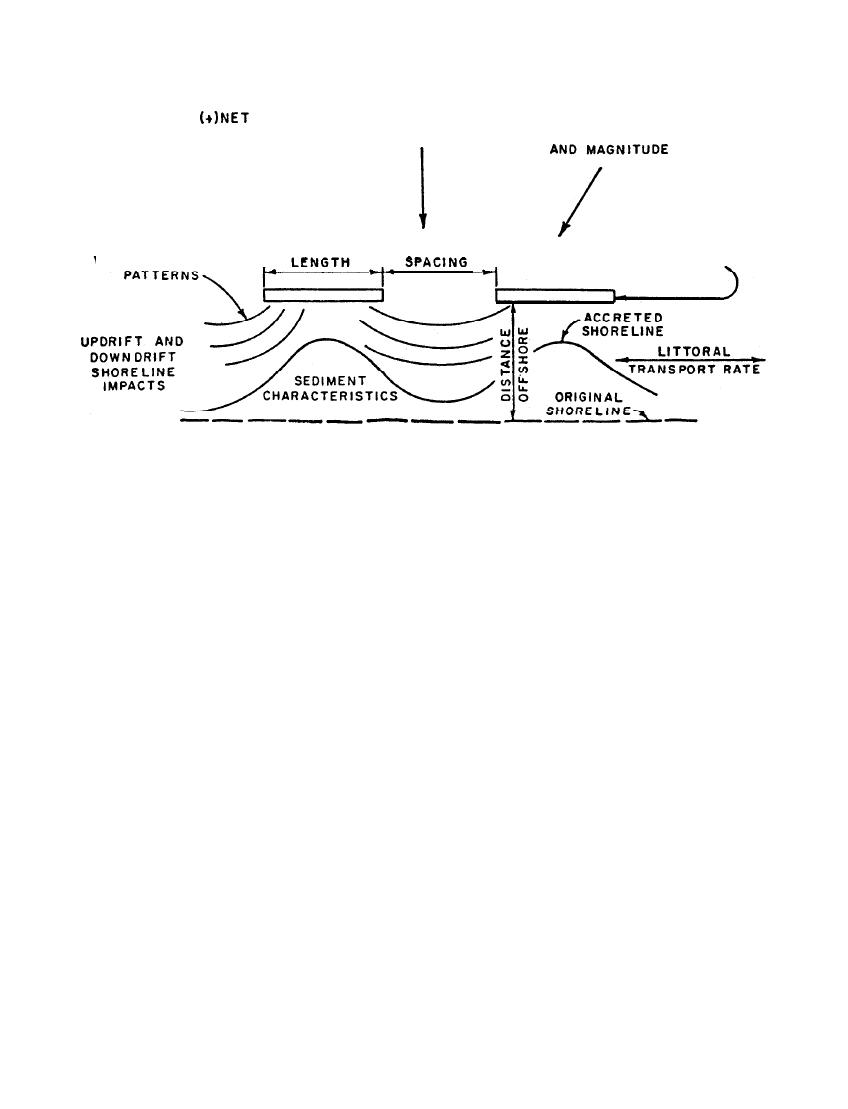

PREDOMINANT

WAVE DIRECTION

LONGSHORE

(-)NET LONGSHORE

AND MAGNITUDE

WAVE DIRECTION

WAVE DIRECTION

AND MAG,NITUDE

BREAKWATER

HEIGHT

WAVE DIFFRACTION

AND POROSITY

Offshore

Breakwater

Design

Considerations

Figure 2.

The magnitude and direction of the predominant incoming waves also play

important

roles.

For instance, large, long-period waves tend to diffract

more into the.lee of a breakwater than do smaller waves, resulting in a more

pointed

shoreline.

Smaller,

short-period waves diffract less, resulting in

a mo're rounded shoreline.

Highly

oblique, p redominant

waves

induce

strong

longshore currents which restrict the amount of accretion in the lee of a

breakwater;

in this case, breakwaters can be orientated normal to the domi-

nant incident wave direction.

Sites with a broad spectrum of wave approach

will require more general protection to the shore.

which are generally less important con-

Breakwater

height

and

porosity,

siderations,

should be designed to reduce the transmitted wave energy enough

to prevent the protective beach from being stripped away and back beach fea-

The degree of transmitted wave energy which the structures

tures

endangered.

Where

tidal

energy

allow will influence the future shoreline configuration.

significant, the potential effect of the breakwater system on nearshore

is

currents should also be considered.

The protective beach itself is an important part of the offshore break-

If the structures are to be placed in a high littoral

water

system

design.

transport rate zone and damage to downdrift beaches due to longshore trap-

ping is a concern, beach fill should be incorporated into the project plan.

The functional design of protective beaches is discussed in CETN-III-11

(March 1981).

3

Previous Page

Previous Page